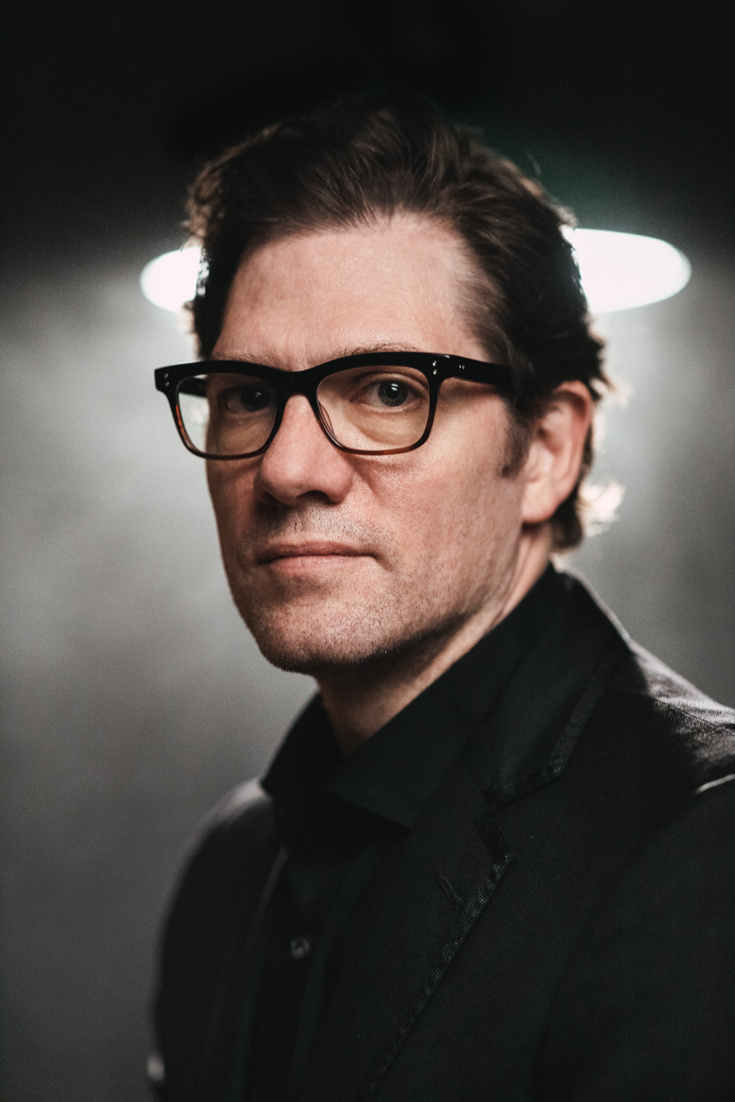

Playwright Adam Rapp on Building a World of Adolescent Extremes for The Outsiders

(Photo by Emilio Madrid for Broadway.com)

The Outsiders was published in 1967, the year before Adam Rapp was born, but he vividly remembers devouring S.E. Hinton’s now-classic YA novel in his dorm room at military school. The tale of the orphaned Curtis brothers and their “Greaser” friends, narrated by 14-year-old Ponyboy, struck a nerve with Rapp, the eldest child of a working-class single mother. Almost four decades after he first encountered the novel, this prolific playwright, novelist, screenwriter and director is making his Broadway debut as a musical book writer (with Justin Levine) in an exhilarating adaptation of The Outsiders.

Known for his fondness for dark material and disaffected characters, Rapp is charmingly cheerful on the topic of his new show, which has been in the works for almost a decade. It helps that his first Broadway production, the 2019 drama The Sound Inside, received six Tony nominations, including Best Play, and his latest novel, Wolf at the Table, was published in March to glowing reviews. As for how he and his baby brother, Anthony, ended up in the top ranks of New York theater, Rapp says simply, “I have no idea.”

You are the ultimate multi-hyphenate writer and director. How does it feel to add musical theater book writer to the list?

It’s a shock, honestly. I was a novelist who became a playwright who fell in love with theater and started directing plays. I had no musical theater training and I’ve never been a performer, so when I was approached about this, I thought, “Wow, they must be confusing me with somebody else.” Then I heard two songs that [Jonathan Clay and Zach Chapman of] Jamestown Revival had written, and I thought, “How can I not involve myself with this?” The music is so beautiful, and it feels very, very honest and sincere in expressing the way teenage boys think about the world.

When did you read The Outsiders for the first time, and what did you love about it?

I read it when I was 15, and it had a profound effect on me. I come from a similar background as Ponyboy. My mother was a single mom raising three kids on a nurse’s salary. We grew up in an apartment complex in Joliet, Illinois, so I identified with the idea of what “family” means when you come from a broken home that’s lower middle class. It was my first reading experience in which I felt seen, and I think a lot of kids feel that way when they read the book.

What was your goal in turning The Outsiders into a musical? What kind of theatrical experience did you envision?

I wanted it to have almost operatic extremes. Adolescent life is so dramatic. Growing up in this country, there is so much pressure to succeed, so much pressure about sexuality, and I wanted the audience to feel that. I said to my collaborators that I wanted this world to be as brutal as it is tender, as bleak as it is beautiful; we needed to fill in all the extremes, because that’s what being 14, 15 and 16 is like.

I love the fact that you provided stage directions for the riveting rumble between the Greasers and their rival gang, the Socs.

I wrote it because I thought the rumble was one of the most successful parts of the movie. We were all on the same page that this should be a non-musical moment. It should be the sound of bodies and fists meeting flesh and boys crying out, with a soundscape to create the mood. I sat next to Matt Dillon [who played tough guy Dallas in the 1983 film version] when he came to see the show, and he was blown away by the rumble. He told me that Francis Ford Coppola was going to delay the rumble a day or two because they were expecting rain, and Matt convinced him to go ahead and shoot it in the rain. I remember how visceral and intense it was, and I thought how cool it would be if at the end of the rumble, you can’t recognize a Greaser or a Soc because they’re all undone by the rain and the mud. [Choreographers] Rick and Jeff [Kuperman] embraced that idea and took it even further, with big moments that are abstracted toward the end, and [director] Danya [Taymor] added some surprising elements.

In agreeing to write the book, did you realize you were taking on the most challenging element in a musical?

I did not, and it could be frustrating. I control almost everything I do when I’m writing a novel or directing one of my plays or working on TV as a showrunner. In this case, I was one of five people trying to tell this story, so it was humbling. You see your scene get winnowed down and absorbed by songs; I used to joke that I started to feel like I was just the gardener. But I’ve come back around to really loving the process. I’ve been hearing this music for more than nine years, and it still makes me emotional. I feel very lucky to have my words living around these songs.

What was it like to meet S.E. Hinton when you traveled to Tulsa with the cast?

I wasn’t anticipating how incredibly powerful that was going to be. I have a young adult novel called 33 Snowfish that made a list of the top 50 books for young adults, and what was number one? The Outsiders! So I was kind of intimidated to meet Susie. She suffers no fools, she says it like it is, she loves to have a drink and a one-on-one talk; she’s salt of the earth. I guess the word for how I felt is privileged. I can’t wait for her to see the show, especially one of the final moments that involves Ponyboy’s notebook. I’m so proud to be part of the team trying to make her novel come to life in a new way.

As if you don’t have enough going on, your latest novel, Wolf at the Table, was just published.

It’s a coincidence that so many things are happening at once. I’ve been working on that novel for a decade. [Inspired by his late mother’s work as a nurse at the prison where John Wayne Gacy was executed, the book is a multigenerational saga of a family harboring a serial killer.] And not only that, the show I ran for Amazon Prime, American Rust: Broken Justice, dropped on March 28. A lot of writers multitask by necessity, because if you want to stay in New York, you have to do more than just write novels unless you’re a bestseller. This month has been insane and exhausting, but I’m glad it’s all out.

What are the odds that two brothers from Joliet, Illinois, would make it to Broadway, one as the star of Rent and the other as the writer of a musical?

You’re telling me! I have no idea. Anthony started acting when he was very young; he was in a couple of national tours, and my mom would stop nursing to help his career. He was always sort of a north star in our family. He’s a registered genius—when he was seven, he took a test and his IQ was like 197. He was two years ahead in school and quit at 16 to go to NYU film school, so I’m not surprised he flourished and found success. To be honest, I’m more surprised that I’ve had any kind of success because I was kind of a knucklehead. I was sent to a military academy for high school, which had nothing to do with theater. I was a jock—I was a basketball player; I ran cross-country; my life was sports. I discovered fiction writing in college, but it wasn’t until I saw Anthony in Six Degrees of Separation in 1991 that I realized plays weren’t just musicals. I saw John Guare’s plays and Nicky Silver’s plays, Sam Shepard and Caryl Churchill, and that’s when I realized theater can do something really interesting and dark and artful. Theater kind of found me. I just lucked into falling in love with the thing that would give me a career.

Well, your distinctive voice is being appreciated now. That must feel good.

Look, when I started out, I didn’t know what I was doing. I didn’t have any training. I was just absorbing everything I could to develop my own aesthetic. I always responded to seeing intense things go down, when you forget you’re watching a scene framed in front of you. If we’re going to fight on stage or have sex on stage, let’s make the audience think it’s really happening! Let’s really go there. That’s what drove me. They’re coming to see a story, but let’s try to make them want to rush the stage.